Terror and terroir by Andrew W. M. Smith

Author:Andrew W. M. Smith [Smith, Andrew W. M.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History, General, Europe, France, Modern, 20th Century, Social History

ISBN: 9781526101129

Google: G225DwAAQBAJ

Publisher: Manchester University Press

Published: 2016-09-19T00:22:16+00:00

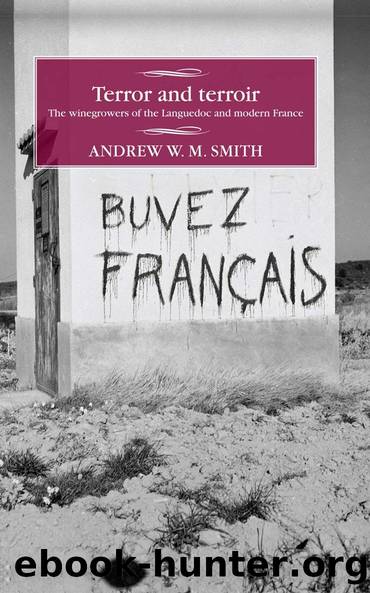

Figure 8 Poster campaigning for the release of Albert Teisseyre

Three weeks after the Montredon shootout, a winegrower called Albert Teisseyre was arrested and charged with âattempted homicideâ,122 a charge which was serious, but not such as to threaten his freedom.

Four years after the events, Teisseyre was arrested again, with sketchy photographic evidence suggesting that it was he that fired the fatal shot. There was outrage that the prosecution had taken so long to arrive in court, with the PCF describing it as a ânew provocation against winegrowers and winegrowingâ.123 Maffre-Baugé promised the support âof all winegrowing organisationsâ.124 The court case spanned the fifth anniversary of the shootings as legal changes complicated proceedings.125 The difficulty lay in determining whether Teisseyre was involved in a political act or a criminal one, with the Peyreffite law of 1981 allowing him to be tried for a criminal charge despite his predating conviction in 1976. This in turn posed serious questions about the CRAV and their role. The case encountered a series of delays, with an original judgment date of November 1983 postponed into 1984.126 Finally, on 2 February 1984 Teisseyre was pardoned under the Amnesty law brought in by Mitterrandâs government in 1981.127 Cases described the amnesty as a victory that was essential to maintain âsocial orderâ, congratulating the courts on reaching a sensible verdict.128 Inevitably challenged in the Appeals court by the prosecutors, the case rumbled on before Teisseyre was fully acquitted in July 1985, a verdict his lawyer described as âhistoricâ.129 This protracted trial revealed the scars that Montredon had left. The amnesty allowed the Midi to come to terms with the human cost of the events, with monuments erected in memory of the fallen.130 The failures of political representation that had driven the Défense movement into a cycle of radicalisation had created monsters and martyrs of ordinary winegrowers. When the dust settled, however, the gaunt Castéra surmised that all that remained was âa shared shameâ.131

Notes

1 P. Martin, âViticulture du Languedoc: une tradition syndicale en mouvementâ, Pôle Sud, 9:9 (1998), pp. 73â77.

2 ADA 98J8, âVivre au paysâ, Midi Libre (02/08/1975).

3 The Occitan cross (Croix Occitane) is the distinctive twelve pointed yellow cross set against a red background which constituted the heraldry of the twelfth-century Counts of Toulouse and represents an early emblem of Occitan nationhood.

4 Interestingly, the picture also displays support for the regionalist disturbances in Brittany occurring at the same time, with a placard reading âBreton peasants â We are with youâ.

5 ADH 406W113, Letter from Union Régionale des Coopératives Agricoles du Midi (11/05/1959).

6 For further discussion of the history of the Félibrige movement and their cultural significance, see P. Martel, Les Félibres et leur temps: renaissance dâoc et opinion, 1850â1914 (Pessac: Presses Universitaires de Bordeaux, 2010); S.Calamel and D. Javel, La Langue dâoc pour etendard: les félibres (1854â 2002) (Toulouse: Privat, 2002). An internal history of the Félibrige was written by its capoué (leader), see R. Jouveau, Histoire du Félibrige (Nîmes: Bené, 1977).

7 COEA, Le Petit Livre de lâOccitanie (Nîmes, 4 Vertats, 1971), p.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

american english file 1 student book 3rd edition by Unknown(617)

Phoenicians among Others: Why Migrants Mattered in the Ancient Mediterranean by Denise Demetriou(613)

Verus Israel: Study of the Relations Between Christians and Jews in the Roman Empire, AD 135-425 by Marcel Simon(595)

Basic japanese A grammar and workbook by Unknown(584)

Caesar Rules: The Emperor in the Changing Roman World (c. 50 BC â AD 565) by Olivier Hekster(582)

Europe, Strategy and Armed Forces by Sven Biscop Jo Coelmont(524)

Give Me Liberty, Seventh Edition by Foner Eric & DuVal Kathleen & McGirr Lisa(501)

Banned in the U.S.A. : A Reference Guide to Book Censorship in Schools and Public Libraries by Herbert N. Foerstel(492)

The Roman World 44 BC-AD 180 by Martin Goodman(480)

Reading Colonial Japan by Mason Michele;Lee Helen;(471)

DS001-THE MAN OF BRONZE by J.R.A(467)

Introducing Christian Ethics by Samuel Wells and Ben Quash with Rebekah Eklund(464)

The Dangerous Life and Ideas of Diogenes the Cynic by Jean-Manuel Roubineau(458)

Imperial Rome AD 193 - 284 by Ando Clifford(457)

The Oxford History of World War II by Richard Overy(456)

Catiline by Henrik Ibsen--Delphi Classics (Illustrated) by Henrik Ibsen(442)

Language Hacking Mandarin by Benny Lewis & Dr. Licheng Gu(414)

Literary Mathematics by Michael Gavin;(409)

Brand by Henrik Ibsen--Delphi Classics (Illustrated) by Henrik Ibsen(401)